The extinction of certain animal species can be attributed to human activities, encompassing overexploitation, habitat destruction, and ecological imbalances. But what animals have humans sent into extinction?

Activities such as overhunting, fishing, and deforestation have been carried out by humans, often driven by an insatiable desire for resources and consumption. The delicate balance of biodiversity is disrupted by the relentless exploitation of natural habitats and ecosystems, pushing numerous species to the brink of extinction.

Contents

- The Wooly Mammoth

- Eurasian Aurochs

- Dodo bird

- Stellar’s Sea Cow

- Great Auk

- Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger or wolf)

- Reversing Extinction

The Wooly Mammoth

The woolly mammoth, a majestic and iconic species of the Pleistocene epoch, faced extinction primarily due to a combination of environmental changes and human activities. These large, hairy elephants roamed vast areas of the northern hemisphere during the last Ice Age. The warming climate, marked by the retreat of glaciers and the expansion of tundra, altered their habitats, leading to a decline in suitable vegetation for the mammoths.

While climatic factors played a significant role of their extinction, human activities, particularly hunting and habitat modification, further hastened their demise. Prehistoric humans, recognising the value of mammoth resources such as meat, bones, and tusks, engaged in extensive hunting, contributing to the decline of mammoth populations. The culmination of environmental shifts and human interactions eventually led to the extinction of the woolly mammoth around 7,500 years ago, marking the end of an era for this majestic species.

Read more: Sheila the Elephant Survived WW2 by Being Taken Home by Her Keeper

1627 – Eurasian Aurochs

A large, wild ox, once prevalent across the steppes of Europe, Siberia, and Central Asia, was the Eurasian aurochs, considered one of the ancestors of modern cattle. Standing at 1.8 meters (6 feet) high at the shoulder with substantial, forward-curving horns, Eurasian aurochs were renowned for their aggressive temperaments and found themselves engaged in battles for sport in ancient Roman arenas.

As a game animal, Eurasian aurochs were excessively hunted and gradually faced local extinction in many areas throughout their range. By the 13th century, populations had declined to the extent that the right to hunt them was restricted to nobles and royal households in eastern Europe.

In 1564, only 38 animals were recorded by gamekeepers in a royal survey, and the last known Eurasian aurochs, a female, met her demise in Poland in 1627 from natural causes.

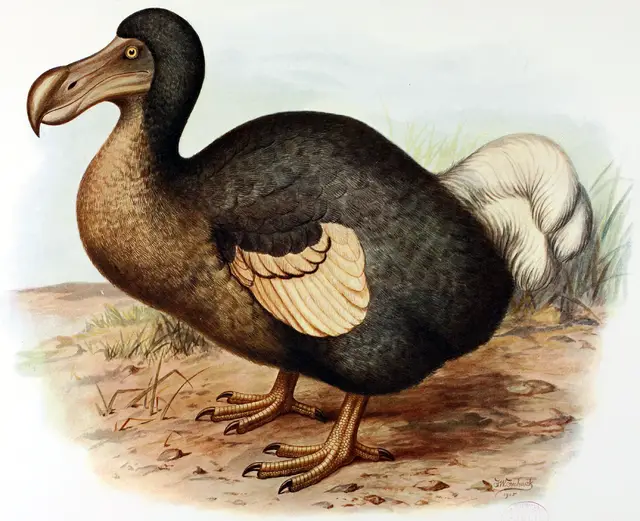

1681 – Dodo Bird

The dodo, a flightless bird indigenous to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, succumbed to extinction primarily due to human activities. Upon the arrival of European sailors around 1507, the dodo, larger than turkeys and weighing approximately 23 kg (about 50 pounds) with distinctive blue-grey plumage and a sizable head, encountered an unforeseen threat. Unfazed by the unfamiliar humans, the dodos quickly became an easy source of fresh meat for Portuguese sailors and subsequent visitors, leading to a rapid decline in their population.

The situation worsened with the introduction of invasive species such as monkeys, pigs, and rats to the island, which further devastated the dodo population by preying on their vulnerable eggs. The last recorded instance of a dodo occurred in 1681, marking the unfortunate end of this unique species, with only scarce scientific descriptions and museum specimens remaining as testament to its existence.

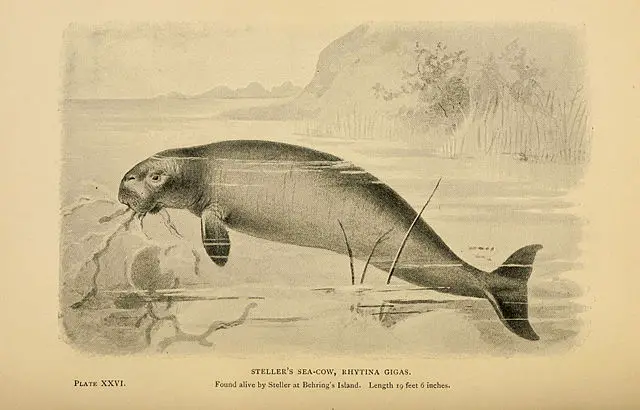

1768 – Stellar’s Sea Cow

Steller’s Sea Cow, a marine mammal that once inhabited the waters of the North Pacific, faced extinction primarily due to overhunting by humans. Named after the naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller, who documented the species in 1741, these massive marine herbivores, related to the manatee, fell victim to intensive hunting for their meat, blubber, and other valuable resources.

With no natural predators in their isolated habitats, the Steller’s Sea Cow population could not withstand the pressures of relentless human exploitation. The animals were particularly vulnerable due to their slow reproductive rates and limited geographical distribution. By the late 18th century, just a few decades after their discovery, Steller’s Sea Cow had been driven to extinction, serving as a poignant example of the profound impact of human activities on vulnerable marine species.

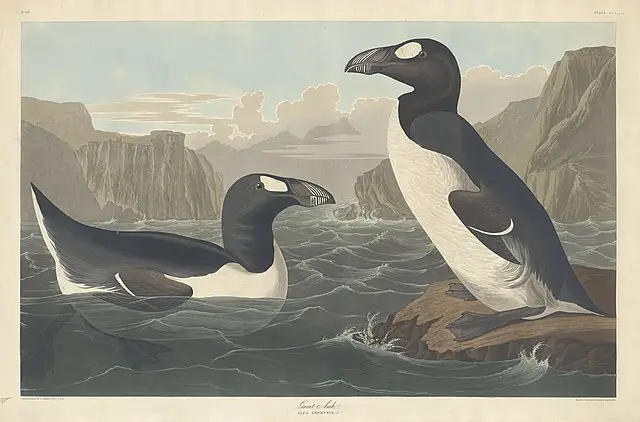

Great Auk

The Great Auk, a large, flightless bird native to the North Atlantic, faced extinction primarily due to human activities during the 19th century. These distinctive birds, resembling penguins, were sought after for their meat, eggs, and feathers, making them easy prey for hunters and collectors.

The introduction of firearms further intensified the rate of exploitation. As human settlements expanded along the coastal areas where the Great Auk bred, the birds found themselves exposed to increased hunting pressure and habitat disturbance. The combination of overhunting, habitat destruction, and the collection of eggs led to a rapid decline in the Great Auk population.

The last confirmed individuals were recorded in the mid-19th century on the remote island of Eldey off the coast of Iceland. The Great Auk’s extinction serves as a poignant reminder of the consequences of unchecked human exploitation on vulnerable species.

1936 – Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger or wolf)

The Thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, faced extinction primarily due to a combination of human persecution, habitat loss, and disease. Indigenous to Australia and Tasmania, these unique marsupials suffered from extensive hunting by European settlers who considered them a threat to livestock. The Thylacine’s perceived threat to domestic animals led to widespread persecution, with bounties offered for their extermination.

Additionally, habitat destruction and fragmentation resulting from agricultural expansion contributed to the decline of their populations. Disease, introduced by European species, further impacted the Thylacine. The last known individual died in captivity in 1936, marking the tragic end of a once-widespread and iconic species. The Thylacine’s extinction underscores the detrimental consequences of human activities on fragile ecosystems and indigenous wildlife.

Reversing Extinction

Advancements in genetic engineering in recent times have prompted discussions about the prospect of resurrecting extinct species. Since the cloning of Dolly the sheep in 1996, scientists have demonstrated the possibility of creating an organism from the DNA contained in a single cell. Museums globally house specimens of extinct animals, preserving their DNA.

The notion of employing DNA to revive extinct species and reintroduce them into their natural habitats raises contentious issues. Determining the criteria for selecting which species to revive poses a challenge, and there are concerns about the potential impact on existing Earthly species. The ethical and ecological implications of resurrecting extinct organisms through genetic engineering remain subjects of ongoing debate.