Most of us associate the Alps with images of wealthy people taking to the slopes for skiing holidays.

We imagine these mountains to be pristine peaks of powdery, white snow, down which rich folk take long runs and then warm up with hot cocoa in a fancy ski lodge at the base of the mountain.

Contents

That image is rapidly changing. As global temperatures rise and snow around the world melts, or doesn’t appear at all even in winter, the Alps are enduring the kind of temperature shift that means skiing may soon be out.

Hiking will be the only game in town if temperatures keep climbing the way they are right now.

Battlefield

But while that reality is discouraging in one context, in a historical context it has meant that war historians, archaeologists and other experts have been granted a once-in-a-career opportunity to see first hand, close up, just what the Alps war zone during the Great War looked like.

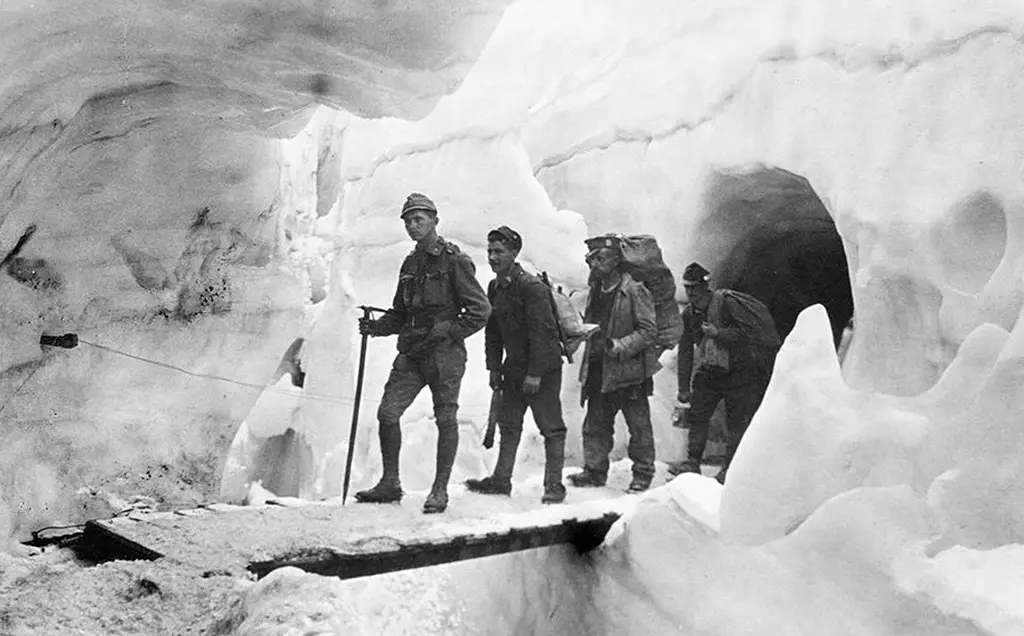

During the first World War, the Austro-Hungarian soldiers hacked their way into glaciers to shelter from enemy fire. It was soon realised that these ice bunkers would also protect and save them from something for more savage than enemy fire and shelling – the weather.

White War

With temperatures falling to -40 and constant avalanches it is stated that 70% of soldiers who lost their lives in the Alps during WW1 were not killed by the enemy, but by the elements. By its very nature the war in the Alps became known as The White War.

Abandoned

On Marmolada Grande Guerra the troops dug over 12km (8 miles) of tunnels and they could accommodate up to 200 soldiers. It was like a mini city and became known as “Città di Ghiaccio” (the Ice City).

The icy complex was an impressive feat of engineering and included kitchens, chapels, storerooms and barracks.

At the end of the war in November 1918 the Ice City was abandoned as troops returned home. Over a period of time and with the natural moment of glaciers, the tunnels and all that what left behind collapsed and was reclaimed by the ice and was entombed forever – or so we thought.

Bunkers

Recently, an Italian professor and a military historian discovered a frozen war museum, of sorts – a trail of World War I artifacts, tunnels and a bunker, long buried beneath the snow on a mountain bordering Switzerland and Italy.

“The artifacts are a representation, like a time machine, of… the extreme conditions of life during the First World War,”

“It’s a sort of open air museum,” said Morosini, who said that five years ago the bodies of two soldiers were found, along with documents that allowed them to be identified and their remains given to their families.

Stelvio Pass, historian Stefano Morosini

As if by sleight of hand, the curtain of snow was pulled away to reveal everything from lanterns to canteens, straw beds to bullets and many more items left behind when the war ended in 1918.

Ironically, the the discovery was made precisely when the 2021 international conference on climate change was happening, in Glasgow, Scotland, in the fall.

The challenge now is getting all the artifacts down from Mount Scorluzzo on the edge of Stelvio National Park quickly, so they are not damaged by exposure to dampness, air and other elements that degrade the materials of which they are made – paper, straw, and metal.

Cannon

This is not the first time discoveries like this have occurred in the Alps. Other artifacts have been found in the Swiss Alps in what was once the war front, the Italians on one side and the Austro-Hungarians on the opposite.

Ultimately, the current team retrieving the items hopes, they will be part of a new war museum in a town at the foot of the Italian Alps, scheduled to open in 2023.

The Platigliole Glacier is also gone now, and the artifacts discovered when it melted are stored in a warehouse in a small town at the foot of a mountain.

Snow and ice are receding all over the world. In Colorado during the week of January 1st, a fire broke out in a small town that engulfed approximately 1,000 buildings.

Usually snowfall prevents fire from spreading, but this year – in a state famous for its skiing – there was not enough snow on the ground to stop the flames.

But sometimes, as in the Italian Alps discovery of the World War I artifacts, there is an upside to the lack of freezing temperatures that keep snow coming. An entire facet of that war is now accessible to military experts and historians, and will one day be available to the public as well.

Puppy

Another example is the melting permafrost in Siberia, which gave scientists and biologists the unprecedented opportunity to examine an almost complete, 18,00 year old wolf pup – fur, skin, teeth and just about everything else – when it was found in 2019.

And so the knowledge that comes from things revealed beneath the snow must be welcomed, and studied.

Another Article From Us: Battlefield Relic, The Only Witness Left Standing to the Battle of Culloden

If you like this article, then please follow us on Facebook and Instagram

No one wants unbridled climate change and the dangers it presents. But when ice and snow disappear, and mankind’s collective past is revealed beneath it, scholars and scientists and historians can, perhaps, learn enough from that past to help prevent new, environmentally costly mistakes in the future.