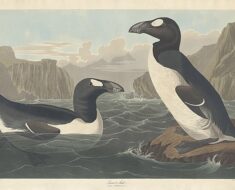

Long before heavy transport and major infrastructure, the logging industry relied heavily on natural riverways to transport logs from forests to sawmills and markets. Timber rafts, enormous in size, were a common sight, carrying millions of feet of timber. These rafts were not just carriers of wood but represented the years of labour by woodsmen and cutters.

Contents

The mid-19th century, particularly in 1857, thousands of men were employed in the lumbering industry on the Wisconsin River alone. The necessity to float lumber through the Wisconsin and down the Mississippi River gave birth to a significant rafting industry.

This industry was sustained by a unique workforce—hardy, industrious men known for their reliability and skill, operating under the guidance of raft pilots. Their journey culminated at sawmills, whereupon they would return upstream via steamboat to start their work all over again.

Evolution

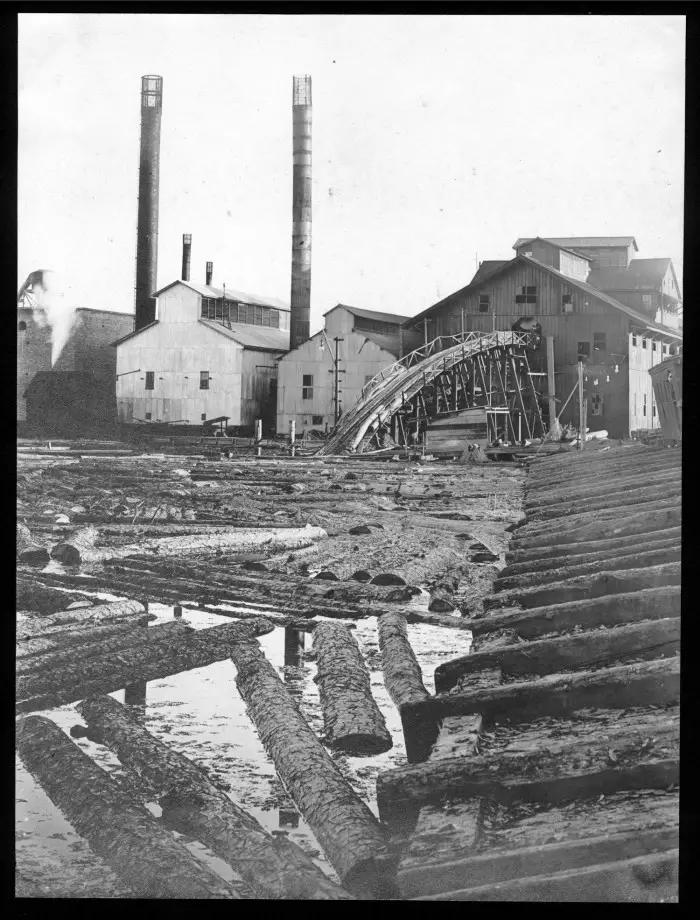

Initially, sawmills were small, water-powered facilities situated close to timber sources, which could later transition to grist mills as agriculture took precedence with the clearing of forests. The evolution in the industry saw the development of larger circular sawmills downstream, with logs floated down to these mills by log drivers.

Read more: Trail Trees: Ancient Native American Sign Posts

In the more smaller stretches of rivers, where large rafts were impractical, logs were driven downstream in a manner similar to cattle droves, showcasing an adaptive approach to the challenges posed by the natural environment.

Since as early as 6 AD, water has been used to power various types of mills. The inherent flow of water in a single direction enables water wheels to capture its kinetic energy for diverse applications. In sawmills, the water wheel is propelled by the water’s force, driving numerous tools essential for handling and processing timber.

Read more: Ajanta Caves Abandoned & Found 1500 Years Later by an Englishman

Certain water wheels, like the overshot type, feature bucket-shaped extensions that capture falling water, enhancing the wheel’s rotation speed and, consequently, its power output.

Construction

Timber rafts could reach enormous dimensions, sometimes extending up to 600 metres (2000 ft) in length, 50 metres (165 ft) in width, and stacked 2 metres (6.5 ft) high. Such rafts bore thousands of logs. For the comfort of the raftsmen, who could number up to 500, logs were utilised to construct cabins and galleys. The rafts were initially manoeuvred using oars and, subsequently, by tugboats.

The construction of rafts varied with the nature of the watercourse. In rocky and windy rivers, the rafts were of simple, yet occasionally ingenious design. For instance, the front parts of the logs were fastened together with wooden bars, while the rear parts were loosely tied. This flexibility allowed the rafts to easily navigate narrow and winding waterways.

Read more: Heavily Decorated Viking Sword X-Rayed

Timber Convoys

Wide and calm rivers, such as the Mississippi River, facilitated the passage of vast rafts in convoys, and they could even be linked together in strings.

This practice was widespread in various parts of the world, notably in North America and along all the principal rivers of Germany. Timber rafting served to connect vast continental forests, as in southwestern Germany via the Main, Neckar, Danube, and Rhine rivers, to coastal cities and states, where early modern forestry and distant trading were intimately linked. Large pines from the Black Forest were known as “Holländer,” named after their trade to the Netherlands.

Timber Raft Bakery

On the Rhine, substantial timber rafts, measuring 200 to 400m in length and 40m in width, comprised several thousand logs. The crew, consisting of 400 to 500 men, included provisions for shelter, bakeries, ovens, and livestock stables, highlighting a comprehensive infrastructure for timber rafting that facilitated extensive interconnected networks across continental Europe.

Read more: Found: 90-million-year-old Rainforest Close to The South Pole

Each crew was accompanied by an experienced boss, often chosen for his fighting skills to manage the strong and reckless men of his team. The overall drive was overseen by the “walking boss”, who moved from place to place to coordinate the various teams, ensuring logs kept moving past problematic spots. Stalling a drive near a saloon frequently led to a cascade of issues with drunken people.

However, the rise of the railway, steamboat vessels, and enhancements in trucking and road networks gradually diminished the prevalence of timber rafting, although it remains significant, for instance, in Finland.